martes, 19 de abril de 2005

Posted by

Unknown

| at

8:41

Tagged as:

Multimedia

,

Teología

Sobre el autor

Sobre el autor

Blog del departamento de Teología del Istic

Perfil

Herramientas

Más vistos

Archivo

Etiquetas

Aborto

(

8

)

Aceprensa

(

1

)

Amor

(

7

)

Anglicanismo

(

2

)

Antiguos

(

75

)

Aquino

(

2

)

Arqueología

(

7

)

Arte

(

1

)

Benedicto XVI

(

34

)

Biblia

(

15

)

Bibliografía

(

6

)

Bien

(

1

)

Bioética

(

11

)

Blog

(

1

)

blogosfera

(

1

)

budismo

(

1

)

celulas madre

(

4

)

ciencia

(

15

)

Comunión

(

5

)

Congreso

(

2

)

Creación

(

1

)

creacionismo

(

1

)

cristianismo

(

1

)

Cristología

(

3

)

Datos

(

1

)

De todo un poco

(

8

)

Dei Verbum

(

1

)

Derecho

(

1

)

Descargas

(

1

)

Diálogo

(

29

)

diccionarios

(

3

)

Dios

(

31

)

Documentos

(

7

)

Eclesiología

(

1

)

Economía

(

2

)

Ecumenismo

(

7

)

Educación

(

1

)

Enciclopedia

(

1

)

Enlaces

(

3

)

Escatología

(

1

)

Espiritualidad

(

6

)

Estudio

(

2

)

Ética

(

1

)

Eucaristía

(

8

)

Europa

(

1

)

Evangelización

(

7

)

evolucionismo

(

1

)

Exégesis

(

5

)

expansión

(

1

)

Fe

(

1

)

Filosofía

(

31

)

Física

(

1

)

Fundamental

(

2

)

Gracia

(

1

)

Griego

(

1

)

Historia de la Iglesia

(

3

)

Historia de las religiones

(

1

)

Homosexualidad

(

1

)

Iglesia

(

13

)

infografía

(

1

)

Inspiración

(

1

)

Islam

(

3

)

Istic

(

1

)

Jerusalén

(

13

)

Jesucristo

(

4

)

judaísmo

(

1

)

Kénosis

(

1

)

Laicidad

(

7

)

Laicismo

(

8

)

Latín

(

1

)

Legal

(

1

)

Liberación

(

1

)

libertad

(

8

)

Libros

(

10

)

Liturgia

(

10

)

Magisterio

(

14

)

Mal

(

1

)

Manuales

(

1

)

Medios de comunicación

(

5

)

Método

(

4

)

Multimedia

(

22

)

Navidad

(

1

)

Noche

(

1

)

Ortodoxia

(

1

)

p2p

(

1

)

Palm

(

1

)

Patrística

(

7

)

Pobres

(

8

)

Poesía

(

4

)

Programas útiles

(

15

)

Psicología

(

1

)

Recursos

(

33

)

Religiones

(

12

)

Revistas

(

3

)

Sociología

(

1

)

solidaridad

(

7

)

Teodicea

(

1

)

Teología

(

90

)

Tiempo

(

1

)

Tradición

(

2

)

Universidades

(

1

)

Valores

(

1

)

web 2.0

(

1

)

Visitas

Teología2.0

Proudly Powered by

Istic (Gran Canaria)

.

RSS

RSS

Like

Like

Twitter

Twitter

2 comentarios :

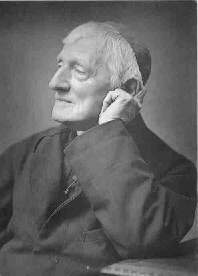

Newman, John Henry

(Londres, 1801- Birmingham, 1890) Prelado británico. Hijo de un banquero, fue párroco anglicano de Saint Mary's de Oxford (1828). Intervino en el movimiento de Oxford, en reacción contra una Iglesia sometida a un Estado secularizado. Para sacudir la apatía del clero anglicano, escribió Oficio profético de la Iglesia (1837). De forma paulatina se fue acercando a la Iglesia romana, hasta pasarse a ella y ser ordenado sacerdote en Roma (1847). Fundador del Oratorio Británico y rector de la Universidad Católica de Dublín (1851-1858), llegó a ser redactor jefe de la revista católica Rambler, que, por su amplitud de miras, desató las iras del cardenal Manning, quien le mantuvo postergado. La elevación de Newman al cardenalato en 1879 fue una tardía reparación. Entre sus obras destaca la Gramática del asentimiento (1870).

Newman, profeta de la Verdad: http://feyrazon.org/newman.htm

A Short Life of Cardinal Newman

{3} This sketch has, by kind permission of the Editor, been epitomized from the masterly biography that appeared in the Tablet, which, to our thinking, was the best in the whole English press. It will shortly be republished in pamphlet form, and every student of Cardinal Newman should read it in its fulness. Much of the matter is suppressed, and much of the beauty and excellence of the original is necessarily lost in this condensed and abridged form.

John Henry Newman was born in the City of London, February 21, 1801, and was baptized a few yards from the Bank of England. His father, according to Mr. Thomas Mozley, "was of a family of small landed proprietors in Cambridgeshire." Mr. John Newman had an hereditary taste for music which came out likewise in his famous son, and was a man of much general culture. It is said that the family was of Dutch Protestant extraction, and originally spelt their name Newmann. Mr. Newman married, in 1800, Jemima Fordrinier, a well-known Huguenot family, long established in the City of London as engravers and paper manufacturers, he himself being a member of the banking firm of Ramsbottom, Newman, and Co. But little is known to us of Newman's first years. He is said to have been intended for the law, and to have kept Terms at Lincoln's Inn. From Memorials of the Past, written by his sister, Mrs. Mozley, we learn that "Henry" was quiet, studious, and devotedly attached to his mother, and that under his grave appearance there lurked a spirit of good-natured irony which now and then made itself felt at the expense of his more impetuous brother, Francis. The family however, though numerous, were united, and held what were then called serious views. In J. H. Newman's blood there must have been a strong taint of Calvinism. Newman says in the Apologia, "I was I brought up from a child to take great delight in reading the Bible; but I had no formed religious convictions till I was {4} 15. Of course I had a perfect knowledge of my Catechism." The Bible he knew almost by heart. His mind and fancy woke together. For he goes on: "I used to wish the Arabian tales were true: my imagination ran on unknown influences, on magical powers, and talismans. I thought life might be a dream, or I an angel, and all this world a deception." In these words many have seemed to discover a key to his after-life. It is certain, indeed, that as a child he was strongly drawn to the supernatural and invisible. Walter Scott himself was always an object of his admiration; nor can we doubt that his stories opened to the future Cardinal a vision of the ancient faith by which he was unconsciously influenced. On the other hand, at fourteen, he read Paine's Tracts against the Old Testament, and found pleasure in thinking of the objections they raised; he became acquainted with Hume's Essays, and copied out some French verses denying the immortality of the soul. But in the autumn of 1816, a great change took place in him. He fell under the influence of a definite creed, and received into his intellect "impressions of dogma" which were never obscured. From the Calvinistic books he learnt the doctrine of "final perseverance." He believed that the inward conversion of which he was conscious, would last into the next life, and that he was elected to eternal glory. He felt a rooted distrust in the "semblance of a material world;" to him there were two only "luminously self-evident beings," himself and his Creator. The dogma of the Trinity was planted deep in Newman's mind. At sixteen, the youthful theologian was supporting each verse of the Athanasian Creed with texts from Scripture. He felt a drawing for years towards missionary work among the heathen (as did his brother Francis), and connected with it, was the deep impression that he was called to a single life. Thus, seventeen years before the Oxford Movement began, there were stirring in the heart of its leader those feelings and convictions of which the outcome, long after, was his submission to the Catholic Church. {5}

But there was another element, not at all compatible with the ancient teaching. From Newton on the Prophecies he learnt that the Pope was Antichrist and the "man of sin" foretold by Daniel, St. Paul, and St. John. That doctrine was the last to leave him; even in 1843 it had still a hold on his imagination, and became to him "a sort of false conscience."

Newman was sent to no public school. He spent some time in an excellent school at Ealing, kept by Dr. Nicholas, to the head of which he rapidly rose. Thence he proceeded to Trinity College, Oxford, where, in 1820, he graduated. But the turning point in his life was his election in 1823 as Fellow of Oriel. To Oriel, Oxford, and England itself the consequences were, in the highest degree, momentous. Oriel was the most distinguished College of the University. Among the Fellows were, or had been, Copleston, Whately, Hawkins, Davison, Keble, Arnold, Pusey, and Hurrell Froude. None of these names is yet altogether forgotten. When Newman entered, it was an extremely critical time in the fortunes of English religion. The fresh influences under which Newman came were represented by Whately and Arnold on the one hand, by Keble and Hawkins on the other. Whately belonged to what was then called "the march of mind," or, in more ambitious phrase, the Noetics. "For about the first thirty years of this century," says Mr. Mark Pattison in his Memoirs, "Oriel contained all the original intellect there was in the University." And not a little of that intellect was, in a narrow English fashion, taking to "free enquiry," which, when it came in contact with religion, was pretty sure to develop the anti-dogmatic principle, and appear as "Liberalism," as Cardinal Newman has always described it. "Liberalism," he said in the famous address on receiving the Cardinal's biretta "is the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another." In other words, religious Liberalism gives to historic forms of belief a merely relative value, according to the circumstances which seem to have produced them; and {6} thus denies the perennial or supreme indefectible authority of any, be it Christian or non-Christian.

The Noetics of 60 years ago were direct ancestors of the Agnostics of today. And the first chapter of Newman's history is taken up with his efforts on behalf of the dogmatic principle—which he then identified with the English Church—against his early Liberal friends. The quondam Low Churchman, who was still an Evangelical, learnt from Whately that the Church was a substantive body or corporation. It was Whately that fixed in him "those anti-Erastian views of Church polity which were one of the most prominent features of the Tractarian Movement." To him, on the other hand, we must partly ascribe it that in 1825-7 Newman "was drifting in the direction of the Liberalism of the day," was "beginning to prefer intellectual excellence to moral," was using "flippant language against the Fathers," and imbibing the sceptical spirit of Middleton in regard to the Early Church Miracles. But it was not his destiny to become a Noetic. "I was rudely awakened from my dream," he writes, "at the end of 1827 by two great blows, illness and bereavement." In the same year he had been named one of the Examiners for the B.A. Degree. He was now Tutor of Oriel, and received from the College the not very valuable, though, as it became in his hands, the celebrated living of St. Mary the Virgin.

Newman had taken Orders in 1824, and his first pastoral duties lay in the parish of St. Clements. He soon began to make an impression on the mind of the University by his sermons; whilst as Tutor he was influencing in a marvelous fashion all the young men he came across. Provost Hawkins took alarm at the views of the relation between tutor and pupils which had been summed up in the phrase, "I consider the college tutor to have a care of souls;" and rather than give way on this point Newman—says Mr. Pattison—"resigned, or rather was turned out." From Hawkins himself, however, he had learnt the great doctrine of tradition upon which is founded the {7} notion of a teaching Church, as likewise the habit of verbal precision which afterwards alarmed his fellow-Protestants as savouring of Jesuistic subtlety. Newman's resignation of his Tutorship was really the beginning of the Oxford Movement. His first volume, the Arians of the Fourth Century, was written, and on resigning his Tutorship he and Hurrell Froude went abroad.

During a journey in Italy in 1833 he composed a large number of the verses afterwards published, including Lead, Kindly Light—a hymn which has become more and more popular in the Church of England, though seldom heard among ourselves. It was a time when the revolutionary movement, springing out of the Three Days of July, seemed to be gathering force, and England herself was going over to Liberalism, religious no less than political. On July 14, 1833, Keble preached the Assize Sermon at Oxford, and took for his subject, "National Apostasy." The impulse was given and it was resolved to unite High Churchmen everywhere in maintaining the doctrine of Apostolic Succession, and preserving the Book of Common Prayer from Socinian adulterations.

"Newman," says Mr. A. J. Froude, and not unfairly from his point of view, "has been the voice of the intellectual reaction of Europe, which was alarmed by an era of revolutions, and is looking for safety in the forsaken beliefs of ages which it has been tempted to despise." Chateaubriand, Joseph de Maistre, Lamennais, F. Schlegel, Rosmini—differing as they did in character, fortune, and natural gifts—were also intellectual voices of what Mr. Froude terms "the reaction;" but upon English-speaking peoples they could none of them have an influence such as it has fallen to Newman's lot to exercise.

Mr. Newman began the Tracts for the Times "out of his own head." They were at first short papers, but grew to be elaborate treatises; and their aim was to uphold "primitive Christianity" as extant in the English Church. The idea of the Via Media began to take form and colour. In the Tracts, in {8} the British Critic, in the Lectures on Justification, and the Prophetic Office, Newman gave it a coherent shape and a philosophy. The scheme looked well on paper, but was impossible to work. From 1833 to 1841 the unwearied genius of Newman was employed in dressing up this phantom. The whole country was roused, but never at any moment had there been a probability of its following in the direction whither Newman pointed. From the beginning he fought a losing battle. But he fought it undauntedly. In 1836 Mr. Hampden was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity. Dr. Hampden, to quote Mr. Mark Pattison again, "had applied the dissolving power of nominalistic logic to the Christian dogmas." It was not conceivable that his appointment should be unopposed. Mr. Newman brought out his Elucidations of the Bampton Lectures; and a vote of censure was passed by Convocation on Dr. Hampden. It was soon the Tractarians' turn to defend their position. Tract Eighty gave great offence by recommending the "principle of reserve," or the economy. It was feared that little by little the Church of England would be secretly indoctrinated with Roman superstition. For years, however, Newman scouted the idea that his methods could lead to Rome. He felt supreme confidence in his position. He wrote many fierce and violent things against the living system which the Papacy controlled and embodied. He was sure that the Pope was anti-Christ.

But a crisis was surely coming. In 1839, Dr. Wiseman published an article in the Dublin Review, drawing out the likeness between the Anglican position and that of the Donatists in the fourth century. Newman read it, was not impressed, and was laying it down, when a friend pointed out to him some words of St. Augustine, quoted in the Review, which had escaped his notice: Securus judicat orbis terrarum. His friend repeated them again and again. They rang in Newman's ears like the knell of his theory. His thought for the Movement was, "The Church of Rome will be found right after all." But he determined {9} to be guided by reason and not by his imagination; had it not been for this severe resolve, he declares he should have been a Catholic sooner than he was. If he must give up the Via Media, he could still fall back upon Protestantism, that is to say, upon the conviction firmly held by him that Rome had leagued herself with deadly error. While in this state of mind he wrote Tract 90, to show that subscription to the Thirty-nine Articles might be made in a Catholic, though not in a Roman sense. He meant the Tract not as a feeler, but as a test. He did not wish to hold office in a Church that would not admit his sense of the Articles. The Tract appeared, and all England was in an uproar.

It is now generally admitted, in the language of Mr. Froude, that "Newman was only claiming a position for himself and his friends which had been purposely left open when the constitution of the Anglican Church was formed." But the Hebdomadal Council condemned the Tract as evading the sense of the Articles and leading to the adoption of religious errors: and on the Bishop of Oxford's desiring that the Tracts should come to an end, Newman submitted and gave up his place in the Movement. Nothing remained except to give up St. Mary's too—a step on which he had been for some time resolved—and go into "the refuge for the destitute," as he playfully termed it, which he was building out at Littlemore. So far, Tract 90 had not been condemned by the Bishops. But in a little while one bishop after another began to charge against him. He recognised in their action that he stood condemned, and he felt it bitterly. To make things worse, his old unsettlement, begun by Dr. Wiseman and St. Augustine, returned upon him in studying the Arian history.

He resigned St. Mary's in the autumn of 1843, and while his old friends of the Via Media were troubled about him, and could not understand his abandoning a view for which he had undergone so much, younger men of a cast of mind less congenial with his own, were coming round him, a new school of {10} thought was rising, and was sweeping the original party of the Movement aside. Among these were Oakeley, Dr. W. G. Ward and Mr. Mark Pattison, "acute resolute minds, who knew nothing about the Via Media, but had heard much about Rome." Mr. Ward made Rome the keynote of the whole controversy. Newman did not know very well what to say. He must, however, have advanced a long way towards Rome, when, some months before resigning St. Mary's, he published in a country newspaper a retractation of the hard things he had uttered against Catholicism in his various writings. It was an act of boldness and humility which has been seldom equalled. The retractation was afterwards inserted in the preface to his Development of Christian Doctrine, where it may still be read. By October, 1843, he could say in a letter: "It is not from disappointment that I have resigned St. Mary's, but because I think the Church of Rome the Catholic Church, and ours not a part of the Catholic Church because not in communion with Rome." He brought out his Sermons on Subjects of the Day, and continued to edit the Lives of English Saints. And so he went on, in a kind of monastic seclusion at Littlemore, till 1845. His work On Development removed the last stumbling blocks from his path, and, on October 9, a day long memorable in the religious annals of England, this, the most distinguished of converts since the Reformation, was reconciled to the Church at Littlemore by Father Dominic, the Passionist.

It was a great shock to the Church of England. But though he shook, he did not convert England. There was an unexampled secession of clergymen, amounting to hundreds; and with them came in course of years certain thousands of the laity. The time was not ripe. If it took ten years to bring Newman himself, it may well take a century or two to bring the nation—unless we imagine a breaking up of social conditions and remodelling of them under entirely fresh circumstances. To the multitude for a long period Newman's conversion was an event without a reason; to the coarse-minded it was the act {11} of insanity. Well nigh twenty years were to elapse before it found an explanation, and then by a happy concurrence of events Newman was allowed to speak, and his countrymen listened. But before and after he had much to endure. The first half of his career, ending in 1845, was crowned by the grace of conversion which made amends for all his trials and disappointments; the second, lasting nearly as long, seemed to him as though it lay under a heavy cloud for the greater part of it, and upon that too a grace came from the hand of religion. For his elevation to the purple had much in it of the joy and beauty of a new life, and gave him, as nothing else could, a home in the hearts of Catholics without distinction of school or party.

On February 23rd, 1846, he finally quitted Oxford, and was called to Oscott by Dr. Wiseman. He stayed there till October, and then set out for Rome where he was ordained priest; his plan of founding an Oratory of St. Philip Neri was approved; and he came back to England on Christmas Eve, 1847. He had no ambitious views, nor could he tell what was in store for him. He lived successively at Maryvale or Old Oscott, at St. Wilfrid's College, Cheadle, and at Alcester-street, Birmingham, where, on June 25, 1849, the Oratory was established. He there spent, as Dr. Ullathorne bears witness, "several years of close and hard work," like the humblest and most heroic of missionary priests. A well-known episode was his charitable ministration at Bilston in 1849, with Father Ambrose St. John and another Oratorian, during a visitation of cholera. They went of their own accord when the Bishop had no other priests to spare.

The restoration of the Catholic Hierarchy in September, 1850, was to have important consequences for Father Newman. He preached his never to be forgotten sermon on the Second Spring at its opening Synod, held in the chapel of St. Mary's, Oscott, a sermon which Macaulay is said to have known by heart and from which he used to recite in tone of enthusiasm. {12} In the foolish excitement about the so-called "Papal Aggression," he was led, to give in the Corn Exchange at Birmingham, those eloquent and forcible Lectures on the Position of Catholics, which, in their combination of humour, sarcasm, and close reasoning remind us of the strength, though they are free from the uncivil ruggedness, of Cobbett. In consequence of a certain page not to be found in the present editions, Dr. Newman was brought into court on a charge of libelling a profligate Italian monk, Dr. Achilli. Witnesses from Italy, Malta, and elsewhere, bore out the charges against Achilli to their full extent; but in the face of the evidence Dr. Newman was found guilty. Even the Times declared that there had been a miscarriage of justice. On January 29, 1853, Sir John Taylor Coleridge sentenced his old friend to a fine of £100, and imprisonment till it was paid. Paid of course it was instantly, but there remained the enormous costs amounting to £12,000. From all parts of Europe, Catholics at once came forward with their contributions, in support of one who had gone through a most unpleasant task in obedience to duty and with no personal motive.

In 1854, Dr. Newman was called from the Oratory, now established at Edgbaston, to be first Rector of the Catholic University in Dublin. But as the work in Ireland, owing to circumstances, had not proved a success, he came back, not unwillingly, in 1858, and henceforth was to live a secluded life in his study at Edgbaston, and there he set up a school which, so far as Catholic discipline would allow, was modelled upon the great public schools of England, and has turned out distinguished alumni.

We come now to the year 1864 and the Apologia. It is an oft-told tale, and perhaps the most interesting literary episode of the last half century. Nor by infinite repetition has it yet been staled. That impetuous anti-Catholic, Mr. Kingsley, in reviewing Mr. Froude's History of England, wrote in Macmillan's Magazine for January, 1864, that "Truth, for its own sake, had {13} never been a virtue with the Roman clergy. Father Newman informs us that it need not, and on the whole ought not to be," and so on. Dr. Newman could not, in justice to himself or the Catholic priesthood, allow such a charge to pass; and he wrote to Messrs. Macmillan, drawing their attention to it as "a grave and gratuitous slander." Mr. Kingsley at once, to Dr. Newman's amazement, took on himself the authorship; and, when asked for proof of what he had alleged, spoke in general terms of "many passages of your writings," and in terms quite as vague, of one of the Sermons on Subjects of the Day, preached in a Protestant pulpit and published in 1844, entitled Wisdom and Innocence. Mr. Kingsley draughted out a paragraph which implied that Dr. Newman had been confronted with definite extracts from his works and had laid before Messrs. Macmillan his own interpretation of them. Nothing of the sort had been done. As an apology, it was even worse; for it left on the reader's mind an impression that by clever verbal fencing the accused had got out of a charge that was substantially true. Dr. Newman published the correspondence and brought out its drift and importance in certain Reflections at the end, which with their exquisite irony and decisive argument, took the world by storm. Mr. Kingsley had the misfortune to reply in a pamphlet, What then does Dr. Newman mean? And the reply came in the shape of an autobiography which has been compared with the Confessions of St. Augustine, and which lifted the quarrel into regions where malice and slander could not subsist. "Away with you, Mr. Kingsley, and fly into space," were the parting words addressed to that unlucky writer, whose fault it had long been to parade himself, something too much, as the "chivalrous English gentleman;" and whose strict honour and hault courage received now a not undeserved castigation.

The Apologia was the history of a mind, and gave the true key to a whole life. His country at once accepted Dr. Newman's account of himself; it replied to Mr. Kingsley by admitting, in the words of Mr. Froude, that "Newman's whole {14} life was a struggle for the truth," and it saw that "he had brought to bear a most powerful and subtle intellect to support the convictions of a conscience which was superstitiously sensitive." As regards his Protestant fellow-countrymen, Dr. Newman became the object of their veneration and attachment; they were proud of him; and, if we may so express it, they condoned his change of religion for the sake of the personal qualities which they now prized at a transcendent value.

On the love and veneration of his Catholic brethren he might surely always count; but the times were difficult and peculiar, discussion was rife, and men whose ways of thought differed from his own were not content altogether with certain expressions in his writing or what they deemed the tendency of his views. But no one ever really doubted him among Catholics; and what controversy there may have been was owing to a wish, on the part of those concerned, to keep the faith in England free from even the remote danger of that "Liberalism" which Dr. Newman was the first to condemn. The year 1869 arrived, and the Vatican Council began. Among those who had been invited to Rome on that occasion as eminent theologians, fitted to advise the Holy See and draw out the Schemata which the Fathers were to consider, was the great Oratorian. He declined, perhaps, among other reasons, because he was engaged on the Grammar of Assent. But he took a keen interest in the Council's proceedings; and, when it was certain that the definition of the Pope's infallibility would be brought forward, friends for whom he was anxious, both Catholic and Anglicans, urged him to use his influence on the other side. He doubted the expediency of a definition, not its possibility; as a matter of fact, he held and taught the doctrine itself, as he says, "long before the Vatican Council was dreamed of;" and he was able, in 1872, to quote the splendid rhetoric in which he enunciated that view absolutely, declaring "the voice of him to whom have been committed the kingdom," {15} to be "now, as ever it has been, a real authority, infallible when it teaches." Not, therefore, on the score of its erroneousness, nor at all on its own account, was Dr. Newman anxious, but he felt for those who came to him, and asked himself whether he ought not to make his feelings public. In this frame of mind he wrote a letter to his bishop, Dr. Ullathorne, which was surreptitiously copied and sent to The Standard. It could not but make a great stir. The author declared, truly enough, that it was a private letter, never meant for publication. And as he had not denied the Papal infallibility before definition, he had no hesitation in accepting the decree of July 18, 1870, which made it an article of faith. Very soon, indeed, circumstances called upon him, not only to proclaim his belief in the dogma, but to defend it and explain its scope and nature.

In 1873 Mr. Gladstone's Government was overthrown on the Irish University question; and he was wroth with the Irish bishops, whom he chose to look upon as acting under orders from Rome; and first in the pages of a magazine, and then in a pamphlet on the Vatican Decrees, of which one hundred and twenty thousand copies were sold in a few weeks, he turned and did what in him lay to rend the militant Catholicism which he deemed his foe. The question was, of course, whether a man who acknowledges the Pope can be loyal to the Queen. Mr. Gladstone did his best, in the face, at all events, of English history, to show that this was impossible. He took the "high priori" road of analysing documents and arguing in the abstract. He declared that Rome had broken with ancient history and modern thought. Catholics had no choice but to reply. Dr. Newman came forward once more; and his last considerable work, the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, showed that his hand had not lost its cunning, nor his eloquence its charm. As of old he was impressive, graceful, lucid, and winning. And the honours of the controversy remained with him; for Mr. Gladstone, in acknowledging the personal loyalty of "the Queen's {16} Roman Catholic subjects," gave up, in fact, the point for which he had contended, namely, that they could not be loyal. Whether they were loyal in consequence or in spite of their religion, was a matter for theorists, not for statesmen. Lookers-on decided that Mr. Gladstone had taken nothing by his motion; and Pius IX. was heard to say that Dr. Newman had done well in answering him.

It was now time that the extraordinary qualities of intellect and heart which for nearly half a century had been making themselves known in this great man should receive the public honours which were their due. The first recognition, as was not unfitting, came from Oxford. In 1877 Dr. Newman was elected Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, which had been "dear to him from undergraduate memories." He returned, in a kind of triumph, to Oxford, after an absence of over 30 years. He became the guest of the President of Trinity, dined at the high table in his academic dress, and visited Dr. Pusey at Christ Church. Once before, since becoming a Catholic, he and Pusey and Keble had met at Hursley Vicarage, and dined there by themselves, September 13, 1865. Keble was now dead, with the reputation of an Anglican Saint; and a great college at Oxford, to which his old friend paid a visit, perpetuates his name and memory. When the second edition of his Development was ready, Dr. Newman dedicated it to the President and Fellows of the College that had restored him to Oxford.

In 1879, Leo XIII. offered Dr. Newman a Cardinal's hat. Addresses of congratulation began to pour in; and, wonderful to say, Protestant England felt that Leo XIII. was doing it an honour in naming a fresh English Cardinal. The change from 1850 was complete and astonishing, for it was not only a token of "Rome's unwearied love" to the English race, but a sign that the old No Popery feeling was, at length, dying away.

Dr. Newman arrived in the Eternal City on April 24th. The formal announcement of his creation as Cardinal Deacon was {17} conveyed to him on May 12 at the Palazzo della Pigna, where a brilliant throng of English and American Catholics, and of high dignitaries, lay and ecclesiastical, surrounded him. On that occasion he delivered an address that will be long remembered. First of all, he spoke of the wonder and profound gratitude which came upon him at the condescension of love towards him of the Holy Father in signalling him out for so immense an honour. He went on to claim for what he might have written, not immunity from error, but an honest intention and a temper of obedience. And then he spoke of the one great mischief to which he had from the first opposed himself,—Liberalism in the Church; and he renewed his protest now against the doctrine, that there is no positive truth in religion. Perhaps the sensation it created was due as much to the clear consistency of a life's history therein displayed, as to the strength and boldness of its enunciations.

The Cardinal of St. George, as he had now become, for the Holy Father assigned to him the ancient Church of San Georgio in Velabro as his title, took leave of Rome at the beginning of June and after a slow journey, broken at Pisa by illness, came back on July 1 to his devoted people at Edgbaston. The ceremony of receiving him was extremely touching, and when he spoke of coming home for good to stay there until he should be called to his long home, many were moved to tears. He changed nothing of his simple habits of life. Addresses came from the English hierarchy, from the Catholic University in Dublin, from colleges and institutions all over the land, from his own congregation, and from far away New South Wales. To each he returned a word of graceful thanks. Later on he was present at the consecration of the new London Oratory, a remarkable era in the development of Catholicism among us. He published also an essay on the inspiration of Scripture which was indirectly occasioned by M. Renan's Souvenirs de Jeunesse; and he gave a short but effective answer to Dr. Fairbairn who had revived, in a haze of metaphysical discussion, {18} the obsolete charge that Cardinal Newman's governing idea was scepticism. During his last years the strength of the master began to fail him, although his mind lost none of its clearness, and he retained an interest, as ever, in the questions and controversies of the day. Writing became a physical effort, but not until his task had been quite fulfilled. The revised edition of his works, including even his laborious version from St. Athanasius, was complete; and he could wait in happy resignation for the end. He had suffered much at various times, and was never robust; but old age came on softly.

His last sermon at the Oratory was delivered three years ago last Easter, although he made a few comments on the 1st of January, 1889, with reference to the Pope's Sacerdotal jubilee. He was also in Church on occasion of the solemn triduo celebrated on July 18-20, in honour of the beatification of Blessed Juvenal of Ancina. This was the last ecclesiastical function in which he took part. He was also among the company who witnessed the Latin play—the Andria, arranged by himself—performed by the boys of the Oratory School. From that time till Saturday, August 9th, there was nothing abnormal in his condition. On Saturday night the Cardinal had an attack of shivering, followed by a sharp rise of temperature, and the symptoms indicative of pneumonia supervened. On Sunday afternoon he rallied somewhat, and recited his Breviary with Father William Neville. On Monday morning August 11th, he lost consciousness. F. Mills, in presence of the community, gave him Extreme Unction. In the evening, at a few minutes before nine, the Cardinal peacefully expired. The body was then vested in full pontifical robes, and conveyed to the Church. Here it lay in state for some days, and great numbers came from all parts of the country to take a last look at the face of him they had loved. The funeral was fixed for Tuesday, August 19th. At eleven o'clock there was solemn Requiem Mass, the Bishop of Birmingham being the celebrant. There were present in all seventeen bishops, and between three {19} and four hundred clergy, and a distinguished company of laity, both Catholic and non-Catholic. The funeral sermon was preached by the Hon. and Right Rev. Dr. Clifford, Bishop of Clifton. After the service at the oratory, the body was escorted along a road, lined with spectators, to the Retreat at Rednal, and laid beside the tomb of Ambrose St. John, the Cardinal's dear friend in life.

We cannot but hope that, with his own Gerontius, the mighty spirit is now saying:

I went to sleep; and now I am refreshed,

A strange refreshment; for I feel in me

An inexpressive lightness, and a sense

Of freedom, as I were at length myself

And ne'er had been before.

Publicar un comentario